In this blog post, Matt East (Talis Education) shares some initial findings from the Active Online Reading project’s international surveys of staff and students.

A key strand of the Active Online Reading project has involved surveying staff and students on their experiences of online reading, both in terms of their personal practice and, in the case of staff, their pedagogies for teaching online reading. The surveys are still open and we have much work to do to analyse the data that we have collected, but we wanted to share a summary of our initial findings in this post.

Demographics and disciplines

To date, we’ve had over 500 responses from staff and students internationally (around 400 of those are from students). Responses were not limited to the UK, with staff from institutions in Germany, Australia, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, USA, and Australia answering our surveys.

38 institutions are represented in responses to the staff survey. Two-thirds of staff responses come from courses classified as Humanities or Social Sciences, with job titles ranging from Professor to Associate Lecturer, as well as Learning Designers, Curriculum Developers, Librarians and Study Skills specialists.

Student responses covered similar geographical areas, with over half of responses (53%) coming from UK universities. Of these responses, 13% of students classified themselves as having a disability that affected their ability to engage in reading.

Initial Findings

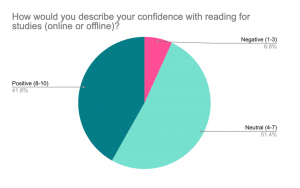

Student confidence vs. academic perceptions

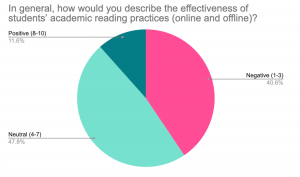

We asked students about their confidence in relation to reading in both physical and digital environments. As the chart below shows, students generally rated their confidence positively, with less than 7% of respondents perceiving their ability as low (a score of 1-3 out of 10). Over 10% of respondents rated themselves as ‘extremely confident’ in their reading.  Conversely, staff responses were more varied, with over 40% of respondents perceiving the effectiveness of students’ reading practice negatively (1-3 out of 10).

Conversely, staff responses were more varied, with over 40% of respondents perceiving the effectiveness of students’ reading practice negatively (1-3 out of 10).  Staff identified a number of factors that impact on the effectiveness of student practice. Intrinsic motivation was seen as critical, whilst transition to Higher Education (HE) was seen as an essential point in helping students to develop reading skills. Specific feedback included that ‘academic language’ (for example language typically found in research papers) is a primary barrier for students, particularly in foundation and first year studies. It was also felt that the perceptions of what ‘good reading practice looks like’ varied considerably across academic disciplines, while institutional support often focussed on fundamental reading skills such as skim reading as opposed to disciplinary-specific capabilities.

Staff identified a number of factors that impact on the effectiveness of student practice. Intrinsic motivation was seen as critical, whilst transition to Higher Education (HE) was seen as an essential point in helping students to develop reading skills. Specific feedback included that ‘academic language’ (for example language typically found in research papers) is a primary barrier for students, particularly in foundation and first year studies. It was also felt that the perceptions of what ‘good reading practice looks like’ varied considerably across academic disciplines, while institutional support often focussed on fundamental reading skills such as skim reading as opposed to disciplinary-specific capabilities.

“Students often struggle with academic reading. In particular, unfamiliar vocabulary or theories can be a big barrier for less confident students, who do not have the skill or confidence to get the gist of a work (or read around unfamiliar material) and then go back and tackle questions or issues with the reading.” (Librarian, UK)

A number of respondents also referred to the ‘impact of social media’, which was seen as reducing students’ attention spans when reading because such platforms encourage or mandate short blocks of text (‘posts’). Unsurprisingly, COVID was judged to have had a major impact on student reading practice, forcing many to adopt digital approaches as their primary means of engaging in academic reading. It was also acknowledged frequently that digital reading literacies were seldom supported institutionally or at discipline-level.

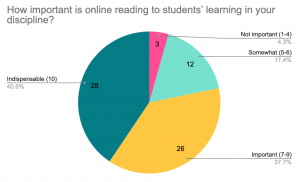

Academic priorities vs. student priorities

Academics mostly felt that reading was an indispensable skill in their subject discipline. Given that the majority of respondents are based in humanities subject areas, this is hardly surprising.

“History is about the creation of historical arguments by reading primary sources and past historical arguments about these sources and events in the past. Reading is at the core of the discipline”. (Associate Professor, History, UK)

There was considerable variation in the extent to which specific tasks aimed at developing reading practice were embedded within curricula: only 20% respondents reported embedding any significant level of reading development activity directly into their modules, with 38% detailing little to no direct focus on this in their teaching.

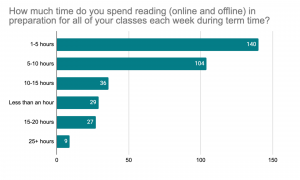

It is clear that while academics view reading as a priority skill, it is not prioritised in curricula. The extent to which students prioritise reading may also reflect this lack of explicit focus. Students’ responses when asked how much time they dedicated to weekly reading for all of their modules are quite startling, especially when contrasted with staff prioritisation and institutional expectations.

Tactics for deepening engagement in reading

Staff reported adopting a wide range of strategies to deepen engagement with reading. Additional activities, such as targeted discussion and guided questioning were the most common, including discussion in class, asynchronous discussion, and discussion via collaborative annotation tools.

Guided questions were seen as essential for sparking discussion and supporting students in targeting their attention, particularly for at earlier levels of study.

Responses indicate that from an academic perspective, making reading tasks more collaborative, by encouraging deeper discussion, annotating, or simply sharing thoughts on subject matter were impactful strategies for deepening students’ focus on reading and their understanding. Students were more polarised on the value of discussion and collaborative reading, a theme to which we will return later in this post. Some, however, seem to have found activities such as collaborative annotation valuable:

“In certain modules we focused on the critical reading of primary and secondary sources. The weekly assignment of various texts essentially forces the student to develop better reading skills. The platform that we viewed these sources in […] even allowed for us to make annotations while we read. I found this to be helpful as I liked to annotate texts that we examined in class.” (Student, Medieval Studies, UK)

It was widely recognised by staff respondents that targeted selection of resources was essential to enable students to focus without becoming overburdened. A limited number of staff respondents reported that the prioritisation of readings was an effective means of scaffolding reading activity.

Other approaches that were mentioned included messaging relating to independent reading activity, developing good reading practises and skills, and signposting additional support, although it was felt that these were typically not effective in encouraging deeper, or more focussed reading.

The challenges of reading online

We asked academics and students what challenges they perceived or experienced in relation to online reading practice. Thematic analysis from staff responses highlighted the following as top perceived challenges:

- Distraction/ lack of concentration

- Lack of core skills (information/digital/critical)

- Lack of support

- General reading challenges

- Screen fatigue

- Impact of social media

- Lack of device ownership / digital poverty

- Poor time management

- Lack of access/availability of resources

- Preference for print

- Learning disabilities

From a ‘reading quality’ perspective, feedback suggested that a lack of skill in deep/critical reading exacerbated other issues relating to reading comprehension and the ability to digest and synthesise information from a variety of sources. A similarly negative impact on the ability to critically appraise information or opinion was also referenced.

“Top three challenges: 1. Reading to then synthesize among diverse academic sources and perspectives; 2. Reading to correctly attribute sources, identify misinformation, substantiate claims; 3. Reading to accurately represent contrary evidence to a claim” (Associate Professor, English, USA)

A wider concern relating to misinformation/disinformation was apparent from qualitative responses, where a lack of criticality was viewed as a broader societal issue. Again, social media was seen as a key contributing factor to this problem.

“Students have a much lower rate of literacy when dealing with long-form texts and longer and more complex argumentative arcs. They have rarely seen information arranged in long texts or engaged with it like that before, nor do they know how to generate long texts with coherent arguments and structures themselves. The media revolution we just went through has also brought with it a steep drop in advanced literacy skills, which is what university study is traditionally based on. Very few of the young people coming through now sat around reading books when they were kids.” (Professor, Theology, Norway)

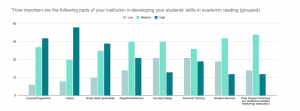

Institutional support vs disciplinary priorities

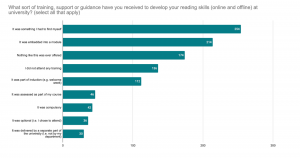

Although, across the sector responsibility for reading skills support is widely spread within institutions, it was felt that courses/programmes, libraries, and study skills/learning development units were the most important areas for developing students’ reading practice.  However, there appear to be challenges around embedding such practises. We asked students about their training/support/guidance relating to reading practises, with the most popular response being that they needed to find additional support themselves. Whilst many responses (over 200) did note that support was embedded in modules, over 170 said nothing at all had been offered to them.

However, there appear to be challenges around embedding such practises. We asked students about their training/support/guidance relating to reading practises, with the most popular response being that they needed to find additional support themselves. Whilst many responses (over 200) did note that support was embedded in modules, over 170 said nothing at all had been offered to them.

The majority of student responses cited basic reading skills as the focus from any additional support that had been offered, but did not define what this covered beyond speed/skim reading tactics and engagement with specific resources types (e.g. journals). This, conversely, was seen as a problem by academics, who highlighted the importance of students developing specific reading skills for specific disciplines.

Qualitative feedback suggests that, when reading skills are embedded in academic courses, students recognise the longer-term value of reading skills and the importance that they have in later study. However, many comments also highlighted the problems that reading support could cause when it was not delivered in a considered manner and with empathy:

“It was one session on reading. It was a bit much for the first years and everyone I know didn’t enjoy it. The lecturer was well-meaning but I think they could’ve taken a different angle, one focusing on extracting key points and summarising rather than using reading to find more reading. It was probably more overwhelming than useful.” (Student, Ancient History, UK)

Academics were mixed on the issue of supporting and developing reading skills. Some thought that this was something that individual academics should take ownership of, while others thought that it was not their role to teach basic skills but rather to focused on more advanced, disciplinary-specific capabilities:

“ I don’t see it as my place to teach general reading skills, but rather work to develop my students’ critical reading skills – argument/evidence etc. I try to ensure my students read actively when preparing for seminars, skills that I hope they will then deploy when reading for essays and for other modules etc.” (Senior Lecturer, History, UK)

Learning from others vs. sharing ideas

Students were polarised on the issue of collaborative learning and reading, especially on the sharing of comments on resources with one another. While many felt that learning from others had considerable value, they were markedly less enthusiastic about sharing their own opinions with others. Qualitative feedback suggested that students valued the validation that came from being able to view the work of peers, enabling them to see differing perspectives and helping to diversity the range of views to which they had access. Qualitative responses suggest that reticence to share ideas with others was based in anxiety, lack of confidence in sharing and concerns about how their comments would be seen by others.

If you could go back…

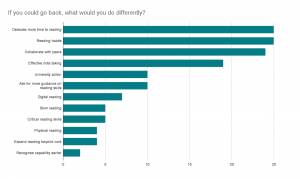

Towards the end of the survey, we asked students to reflect on their university experience and to tell us what they would change about their approach to reading.

Responses spanned many areas, from simply prioritising and dedicating more time to reading, to creating good reading habits early on, including adopting a regular pattern of reading, finding good physical environments to focus on reading, and discussing/collaborating more with peers around readings. Note taking was also highlighted as an area of weakness that had not been developed early enough. It should also be noted that gaps in institutional support were also noted, respondents stressing that the university should have done more to signpost, embed and prioritise key literacy skills within curricula from the start of the course. Some students did recognise, however, that asking for help earlier would have been beneficial.

Other responses spoke more of specific points of reflection. For example, wanting to spend more time reading physical (or digital) books, reading more widely around the subject, and being more confident with personal reading capability.  Students also made recommendations to their institutions. A number of comments suggested dedicating time to developing key academic reading skills, but also providing timetabled collaborative reading (‘guided reading’ sessions).

Students also made recommendations to their institutions. A number of comments suggested dedicating time to developing key academic reading skills, but also providing timetabled collaborative reading (‘guided reading’ sessions).

Finally, students recommended further support on good practice in digital reading, namely guidance around avoiding distraction, developing healthy reading practices and identifying/utilising healthy reading environments for deep thought and comprehension.

What does this mean?

Our preliminary results suggest that reading is seen as critically important, yet largely underdeveloped, skill in Higher Education. In addition, critical reading/literacies were seen as universally important for this generation of university students due to a range of social changes. However, there appears to be a disconnect between what Is offered to students by universities and what academics in specific disciplines require.

“I appreciated the chance to think about this. I have realised it is something that is very neglected which – prima facie – seems problematic.” (Lecturer, Philosophy, UK)

Institutional support for the development of digital reading skills varies dramatically. Where available, such support could be signposted within courses more effectively. Course teams might also consider how they prioritise and integrate support and training to the development of disciplinary reading skills. The first year undergraduate level is critical to developing such key skills, partly because of the need to induct students into new disciplinary expectations about academic literacy and partly to correct misconceptions about what ‘good’ looks like at university level.

In this regard, managing, and in some cases challenging, student perception is an interesting challenge. In general, students perceive their ability positively. But the academics who teach and are responsible for inducting them into new disciplinary cultures are more negative on this issue. Encouraging students to engage in some form of self-reflective mapping at the start of their studies would be desirable here, as might some staff development around the benchmarking of student capabilities (i.e. meeting students ‘where they are’ rather than viewing their skills in deficit terms).

What’s next?

We will continue to analyse these findings, initially segmenting by discipline and year of study and comparing staff and student responses. Further project activity is running alongside this survey, details of which can be found on the project website here. Our research has already highlighted some key themes for further investigation around critical literacies, embedding and signposting of support, and student self-efficacy. We will no doubt find out more!

Matt presented an earlier versions of this research at the Talis Insight APAC conference on 19 January 2022, slides and a recording of which are available. Jamie and Matt outlined some interim findings from the student survey in a blog post in mid-December 2021 (here).

One Reply to “What we have learned so far from the Active Online Reading surveys”